|

| Detail from 1974 Staff Art Show sign |

by F.T. Rea

On

a pretty day in July of 1971, I went to a construction site on the

north side of the 800 block of West Grace Street. It was mostly a big

hole in the orange ground between two old brick houses. A friend had

tipped me off that she’d heard the owners of the movie theater set to

rise from that hole were looking for a manager who could write about

movies. Most importantly, she said they wanted to hire a promotion-savvy

local guy.

Chasing the sparkle of that opportunity I

met David Levy at the construction site. He was the Harvard-trained

attorney who managed the Biograph Theatre at 2819 M Street in

Washington. D.C.

Levy was one of a group of five men

who had opened Georgetown’s Biograph in what had previously been a car

dealership in 1967. Although none of them had any experience in show

biz, they were smart young movie lovers whose timing had been impeccable

-- they caught a pop culture wave. The golden age of repertory cinema

was waxing and they picked the right town.

With their

success in DeeCee a few years later they were looking to expand. In

Richmond’s Fan District they thought they had discovered the perfect

neighborhood for a second repertory-style cinema.

A

pair of local players, energy magnate Morgan Massey and real estate

deal-maker Graham “Squirrel” Pembroke, acquired the land. They agreed to

build a cinderblock building just a stone’s throw from VCU’s academic

campus for the Biograph partners to rent. The cinema's owners had

decided to use the same longtime cinema-related name in Richmond as they

had in Georgetown. If it was good enough for D.W. Griffith it was good

enough for them a second time.

Some 10 weeks after my

first meeting with Levy he offered me the manager’s position. I don’t

remember how many competitors he said I beat out, but I can remember

trying not to reveal just how thrilling the news was. At 23-years-old, I

couldn’t imagine there was a better job to be had in the Fan District.

At the time I was working for a radio station, so I had to keep it a

secret for a while.

Levy and I got along well right

away and we became friends who trusted one another. He and his partners

were all about 10 years my senior.

Three years after

Richmond Professional Institute and the Medical College of Virginia had

merged to become Virginia Commonwealth University in 1968, there were

few signs of the dramatic impact the university would eventually have on

Richmond. Although film societies were thriving on campus in 1971, the

school was offering little in the way of classes about movies or

filmmaking. A few professors occasionally showed artsy short films in

their classes.

Mostly, independent and foreign features

didn’t come to Richmond. So, in 1971, the coming of the Biograph

Theatre to Grace Street offered hope to optimistic film buffs that even

in conservative Richmond the times were indeed a-changing.

My

manager’s gig lasted until the summer of 1983. Grace Street’s Biograph

Theatre closed four years later. A hundred miles to the north the

Biograph on M Street closed in 1996. David Levy died in 2004.

In

2014 there’s a noodles eatery in same building that once housed the

repertory cinema I managed for 139 months. Now it’s the oldest building

on the block.

*

On

the evening of Friday, February 11, 1972, the venture was launched with

a gem of a party. In the lobby the dry champagne flowed steadily as the

tuxedo-wearers and those outfitted in hippie garb happily mingled. A

trendy art show was hanging on the walls. The local press was all over

what was an important event for that bohemian commercial strip. The

feature we presented to the invited guests was a delightful French

war-mocking comedy — “King of Hearts” (1966); Genevieve Bujold was

dazzling opposite the droll Alan Bates.

With splashy

news stories about the party trumpeting our arrival the next night we

opened for business with a double feature: “King of Hearts“ was paired

with “A Thousand Clowns“ (1965). Every show sold out.

The

Biograph’s printed schedule, Program No. 1 was heavy on documentaries.

It featured the work of Emile de Antonio and D.A. Pennebaker, among

others. Also on that program, which had no particular theme, were

several titles by popular European directors, including Michaelangelo

Antonioni, Costa-Gavras, Federico Fellini, and Roman Polanski.

Like the first one, which offered mostly double features, each of the next few programs covered about six weeks.

Baby

boomers who had grown up watching old movies on television had learned

to worship important movie directors. Knowing film was cool; it could

get you laid.

The fashion of the day elevated certain

foreign movies, selected American classics, a few films from the

underground scene, etc., to a level above most of their more accessible

Hollywood counterparts. As I read everything I could find about what was

popular, film-wise, in New York and San Francisco I learned the

in-crowd viewed most of Hollywood’s then-current products as either

laughingly naive or hopelessly corrupt.

Or both.

What

my job would eventually teach me was how few people in Richmond

actually saw it that way in 1972. After the opening flurry of interest

in the new movie theater, with long lines to nearly every show, it was

surprising to me when the crowds shrank dramatically in the months that

followed.

As VCU students had been a substantial

portion of the theater’s initial crowd the slump was chalked off to warm

weather, exams and then summer vacation. In that context the first

summer of operation was opened to experimentation aimed at drawing

customers from beyond the immediate neighborhood.

That

gave me an opportunity to do more with a project Levy had put me in

charge of developing, using radio to promote it -- Friday and Saturday

midnight shows.

By trial and error we learned it took

an offbeat movie that lent itself to promotion. Early midnight show

successes were “Night of the Living Dead” (1968), “Yellow Submarine”

(1968), “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” (1971), and an underground twin bill

of “Chafed Elbows” (1967) and “Scorpio Rising” (1964).

With

significant input from the theater’s assistant manager, Chuck Wrenn,

who was a natural promoter, off-the-wall ad campaigns were designed

in-house. There were two essential elements to those promotions:

- Wacky radio spots had to be created and run on WGOE, a popular AM station aimed directly at the hippie listening audience.

- Distinctive handbills needed to be posted on utility poles, bulletin boards and in shop windows in high-traffic locations.

Dave DeWitt produced the radio commercials. In his

studio, Dave and I frequently collaborated on the making of those spots

over six packs of Pabst Blue Ribbon. Most of the time we went for

levity, even cheap laughs. Dave was masterful at producing radio

commercials; the best I‘ve ever met.

Now DeWitt lives in New Mexico and is known as the

Pope of Peppers. He has written dozens of cookbooks and countless articles about food.

|

| Handbill for the event |

On September 13, 1972, a George McGovern-for-president benefit was

staged at the Biograph. Former Gov. Doug Wilder, then a state senator,

spoke. We showed "Millhouse" (1971), a documentary that put President

Richard Nixon in a bad light.

Yes, I had been warned

that taking sides in politics was dead wrong for a show business entity

in Richmond. Taking the liberal side only made it worse. But the two

most active partners who were my bosses, Levy and Alan Rubin, who was a

geologist turned artist, were delighted with the notion of doing the

benefit. They were used to doing much the same up there. So with the

full backing of the boys in DeeCee I never hesitated to reveal my

left-leaning stances on anything political.

Also in

September “Performance” (1970), a somewhat overwrought but well-crafted

musical melodrama -- starring Mick Jagger -- packed the house at

midnight three weekends in a row. Then a campy, docu-drama called

“Reefer Madness” (1936) sold out four consecutive weekends.

The

midnight shows were going over like gangbusters. To follow “Reefer

Madness” what was then a little-known X-rated comedy, “Deep Throat”

(1972), was booked as a midnight show. While we had played a few films

that were X-rated, this was our first step across the line to hardcore

porn.

As “Deep Throat” ran only an hour, master

prankster Luis Buñuel’s surrealistic classic short film (16 minutes),

“Un Chien Andalou” (1929), was added to the bill, just for grins.

Although I can’t remember whose idea it was to play “Deep Throat” in the

first place, it may have been mine. But I’m pretty sure it was Levy who

wanted to add “Un Chien Andalou” to the bill.

It

should be noted that like "Deep Throat," Buñuel’s first film, was also

called totally obscene in its day. Still, this may have been the only

time that particular pair of outlaw flicks ever shared a billing ...

anywhere.

A few weeks after “Deep Throat” began playing

in Richmond, a judge in Manhattan ruled it was obscene. Suddenly the

national media became fascinated with it. The star of "Deep Throat,"

Linda Lovelace, appeared on network TV talk shows. Watching Johnny

Carson pussyfoot around the premise of her celebrated “talent” made for

some giggly moments.

Eventually, to be sure of getting

in to see this midnight show, patrons began showing up as much as an

hour before show time. Standing in line on the brick sidewalk for the

spicy midnight show frequently turned into a party. There were nights

the line resembled a tailgating scene at a pro football game. A

determined band of Jesus Freaks took to standing across the street to

issue bullhorn-amplified warnings of hellfire to the patrons waiting in

the midnight show line that stretched west on Grace Street. It only

added to the scene.

Playing for 17 consecutive

weekends, at midnight only, “Deep Throat” grossed over $30,000. That was

more dough than the entire production budget of what was America’s

first skin-flick blockbuster.

The midnight show’s

grosses conveniently made up for the disappointing performance of an

eight-week program of venerable European classics at regular hours. It

included ten titles by the celebrated Swedish director, Ingmar Bergman.

The same package of art house workhorses played extremely well up in

Georgetown, underlining what was becoming a painfully underestimated

contrast in the two markets.

|

| Handbill for the Richmond premiere in 1973 |

Even more telling, over the early spring

of 1973 a series of imported first-run movies crashed and burned. The

centerpiece of the festival was the premiere of the Buñuel masterpiece,

“The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” (1972). In what Levy and I then

regarded as a coup, gambling it would win the Best Foreign Film Academy

Award, he booked it in advance to open in Richmond two or three days

after the Oscars were to be handed out.

We had guessed

right, “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” took the Oscar, but it

flopped in Richmond. The one-year-old cinema’s management team was more

than bummed out.

We were stunned by the extent of our miscalculation.

Money

had been put up in advance to secure a print, which was in demand

because it was doing brisk business in most other cities. The failure of

this particular booking and the festival that surrounded it finally

forced a serious reassessment of what had been the original plan. The

Georgetown Biograph couldn’t prop up its Richmond counterpart forever.

*

To

stay alive Richmond’s Biograph needed to make adjustments in it’s

booking philosophy. After much fretting on the phone line between M

Street and Grace Street the Faustian deal was struck -- another film was

booked that had been made by the director of “Deep Throat,” Gerard

Damiano. Significantly, this time the picture's distributor imposed

terms calling for “The Devil in Miss Jones” (1973) to play as a

first-run picture at regular show times, every night, rather than as a

midnight-only attraction.

At this point no one could

have anticipated what we were setting in motion by agreeing to expand

the availability of “adult movies” beyond the midnight hour. As we

hadn't been promoting our midnight shows in the same way we did our

regular fare, for the first time the title and promotional copy for a

skin flick was included on a Biograph program.

Then an

aggressive young TV newsman took Biograph Program No. 12 to Richmond's

new Commonwealth’s Attorney, Aubrey Davis. The reporter asked Davis what

his office was going to do about the Biograph’s brazen plan to run such

a notorious film, especially in light of the then-freshly-minted Miller

Decision on obscenity by the Supreme Court. (Miller basically allowed

communities to set their own standards for obscenity.)

Eventually,

the provocateur got what he wanted from the prosecutor -- a quote that

would fly as an anti-smut sound bite. Other local broadcasters jumped on

the bandwagon the next day. By the mid-summer evening “The Devil in

Miss Jones” opened in Richmond it had already become a well-covered

story.

Once again I saw what publicity could do. Every show sold out and a wild ride began. Matinees were added the next day.

On

the third day all the matinees sold out, too. By the fourth day the

WRVA-AM traffic-copter was hovering over the Biograph in drive time,

giving live updates on the length of the line waiting to get into the

theater. The airborne announcer helpfully reminded his listeners of the

upcoming show times.

Well, that did it!

The

following morning a local circuit court judge asked for a personal look

at what was clearly the talk of the town. Management cooperated with

his honor’s wishes and the print was schlepped down to Neighborhood

Theaters’ private screening room, at 9th and Main Streets, for the

convenience of the judge.

As Judge James M. Lumpkin

admittedly hadn’t been out to see a movie in a theater since sometime in

the 1950s, this particular moving picture rubbed him in the worst way.

Literally red-faced after the screening, the outraged judge looked at

Levy and me like we were from Mars.

Maybe Pluto.

Lumpkin

promptly filed a complaint with the Commonwealth’s Attorney and set a

date for issuing a Temporary Restraining Order, to halt further showings

as soon as possible.

The next day a press conference was staged in the Biograph’s lobby to make an announcement.

Every

news-gathering outfit in town bought the premise and sent a

representative. They acted as if what was obviously a publicity stunt

was news because it served their purpose to play along. After DeWitt --

who was then representing the theater as its ad agent -- laid out the

ground rules and introduced me to the working press, I read a prepared

statement for the cameras and microphones. (No record of this

performance is known to exist.)

The gist of it was that

based on demand -- sellout crowds -- the crusading Biograph planned to

fight the TRO in court. Furthermore, the first-run engagement of “The

Devil in Miss Jones” would be extended -- it was being held over for a

second week.

During the lively Q & A session that

followed, when Dave scolded an eager scribe for going too far with a

follow-up question, it was tough duty holding back the laughing fit that

would surely have broken the spell we trying to cast over the

reporters.

The TRO stuck, because Judge Lumpkin still

had all the say-so. “The Devil in Miss Jones” grossed about $40,000 in

the momentous nine-day run the injunction halted. Technically, the legal

action was against the movie, itself, rather than anyone at the

Biograph. Which obviously suited me just fine.

The

trial opened on Halloween Day. Lumpkin served as the trial judge too. I

was surprised that the person whose original complaint to the

Commonwealth’s Attorney had set the whole process in motion could then

hear the case. Objections to that affront to justice fell on Lumpkin’s

deaf ears.

*

On

November 13, 1973, Lumpkin put all on notice: If you dare to exhibit

this “filth” to the public, then stand by for certain criminal

prosecution. So it was that “The Devil” was banned by a judge in

Richmond, Virginia.

The plot to answer the judge's

decree was hatched in early January of 1974 in the office on the second

story, next to the projection booth. Having finished the box-office

paperwork, or whatever, I was browsing through a stack of newly acquired

16mm film catalogs.

As it was after-hours, the scent

of recently-burned marijuana may have been in the air when a particular

entry -- “The Devil and Miss Jones” -- jumped off the page. It was

instantly obvious to me the title for that 1941 RKO light comedy had

been the inspiration for the banned X-rated movie’s title -- “The Devil

in Miss Jones.”

It

should be noted that the public had yet to be subjected to the endless

puns and referential lowbrowisms the skin-flick industry would

eventually use for titles. This was still in what might be called the

seminal days of the adult picture business. Culturally, because there

was still a blur in the line between edgy underground films and outright

porn the somewhat oxymoronic term "porno chic" was in currency. It

didn't last long.

The prank's plan called for using

the upcoming second anniversary as camouflage. Early on, DeWitt and the

theater’s resourceful assistant manager, Bernie Hall, were in on the

scheming/brainstorming in the office. Then, in a deft stroke --

suggested by Alan Rubin over the phone -- a Disney nature short subject,

“Beaver Valley” (1950), was added to the birthday program, to flesh it

out.

The stunt’s biggest problem was security. The

whole scheme rested on the precarious notion that the one-word

difference in the two titles, which spoke of the Devil's proximity to

Miss Jones, simply wouldn’t be noticed. It was something like hiding in

plain sight. We believed people would see what they wanted to see, but

the staff fully understood the slightest whiff of a ruse would mean our

undoing.

Thus, absolutely no one outside our group could be told anything. No one.

The

Biograph announced in a press release on DeWitt’s ad agency letterhead

that its upcoming second anniversary celebration would offer a free

admission show. The titles, “The Devil and Miss Jones” and “Beaver

Valley,” were listed with no accompanying film notes. Birthday cake

would be free, too!

Somehow, a rumor began to circulate

that the Biograph might be outmaneuvering the court’s decree by not

charging admission. The helpful rumor found its way into print -- the

street gossip section of The Richmond Mercury. I don't know if they knew

what was really going on, or not.

The

busier-than-ever staff fielded all inquires, in person or over the

telephone, by politely reciting the official spiel, which amounted to:

“We can tell you the titles and the show times. The admission will be

free. No further details are available.”

The evening

before the event the phones were ringing off the hook. Reporters were

snooping about. One, in particular, stuck around trying to claw his way

toward the key to the mystery. In the lobby, as I manned my familiar

post at the turnstile, in a conspiratorial tone he said: “It has

something to do with the title, doesn‘t it?”

Uh-oh! He was getting too close. To fend him off I decided to take a chance.

So,

talking like one spy to another, I told the newsman that what was going

to happen the next day would be a far better news story than a story of

spoiling it the day before -- that is, if there really is a trick of a

sort in the works.

Gambling that it would work, I asked

him to leave it alone and trust that once it all unfolded he wouldn't

regret it. Fortunately, he agreed to say nothing and he kept his word.

His identity must remain a secret.

.jpg) |

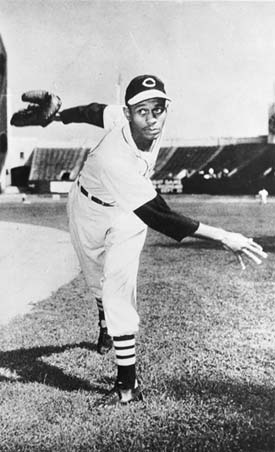

| Feb. 11, 1974: 800 block of W. Grace St. |

Up until the box office opened no one else outside

our tight circle appeared to have an inkling of what was about to

happen. Amazing as it may sound, the caper’s security was airtight. It

was absolutely beautiful teamwork!

On

the day of the event the staff decorated the lobby with streamers and

balloons. We laid out the birthday cake. We tested the open keg of beer,

just to make sure it was good enough for the patrons waiting in line to

drink. Spurred on by hopes the Biograph was about to defy a court

order, by lunch time the end of the line along Grace Street was already

reaching Chelf's Drug Store -- which meant about 500 people.

It was suggested to me that we could eventually have a riot on our hands. What would happen if we lost control of the situation?

Nobody knew. That’s what made it so exhilarating!

My

collaborators on the staff that one-of-a-kind night on the job were:

Bernie Hall (assistant manager); Karen Dale, Anne Peet and Cherie Watson

(cashiers); Tom Campagnoli and Trent Nicholas (ushers); Gary Fisher

(projectionist). Some dressed up in costumes. Trent wore a clown mask.

In case trouble broke out he wanted to be able to take it off and

disappear into the lynch mob.

The box-office for the

6:30 p.m. show opened at 6 p.m. By then the line of humanity stretched

almost completely around the block. It took every bit of a half-hour to

fill our 500-seat auditorium. We turned away at least six or seven times

that number.

The sense of anticipation in the air was

electric as the house lights in the auditorium began to fade. Outside,

on the sidewalk, many of those who couldn't get in to the first show

stayed in line for the second show at 9 p.m.

The prank

unfolded in layers. Some caught on and left while “Beaver Valley” was

running. Most stayed through the first few minutes of “The Devil in Miss

Jones.” Only about a third of the crowd remained in their seats through

both movies. Afterward, there were lots of folks who said it was the

funniest prank that had ever happened in Richmond.

Of

course, a few hardheads got peeved. But since admission had been free,

as well as the beer and cake, well, there was only so much they could

say.

Even though those in line for the second show were

told about the hoax by people leaving the first show, the second show

packed the house, too. By then it seemed a lot of people just wanted to

be in on a unique event, to see what would happen and be able to

(honestly) say they were there.

The rush that came

from living in the eye of that day’s storm of activity was intense, to

say the least. After the second show emptied out, gloating over the

utter success of the gag, as the staff and assorted friends finished off

the second keg, was as good as it gets in the prank business.

|

| The birthday cake was free while it lasted |

Meanwhile, thoroughly amused reporters

were filing their stories on what had happened at the Biograph. The next

day wire services and broadcast networks picked up the story. We

returned to business as usual with an Andy Warhol double feature.

A

few days later NPR’s All Things Considered went so far as to compare

the Biograph’s second anniversary prank to Orson Welles’ mammoth 1938

radio hoax. Which was fun to hear, but I had the good sense to tell the

interviewer that in comparison our stunt was "strictly small potatoes."

Congratulatory

mail came in from all over the country. Six months later the Biograph

closed down for a month to be converted into a twin cinema. With two

screens to fill the manager’s job became more complicated. As an

independent exhibitor, prank or no prank, it wasn’t always easy to rent

enough product to fill two screens. The repertory “mission” become

increasingly blurred over the next few years.

Thinking

back about what an effort it took just to keep the Biograph's doors

open in those days, now it seems like it was all sort of an elaborate

stunt … pranks for the memories.

* * *

Ed. Note: This piece is an excerpt of F.T. Rea's "Biograph Times," a work in progress, soon to be published.

.jpg)